You care about your team. That’s not the problem.

The problem is that caring has started to feel like a trap. When you want to set a boundary, you worry you’ll come across as cold. When you want to push back on a request, you second-guess whether you’ll be seen as unreasonable. Every time you want to say no, you recoil from the fallout.

So instead, you say yes. Again. And the work piles up. The requests multiply. The resentment builds.

Here’s what nobody tells high-empathy leaders: boundaries aren’t the opposite of care. They’re the structure that makes care sustainable.

You don’t need to choose between being empathetic and being effective. You need a way to hold both at the same time.

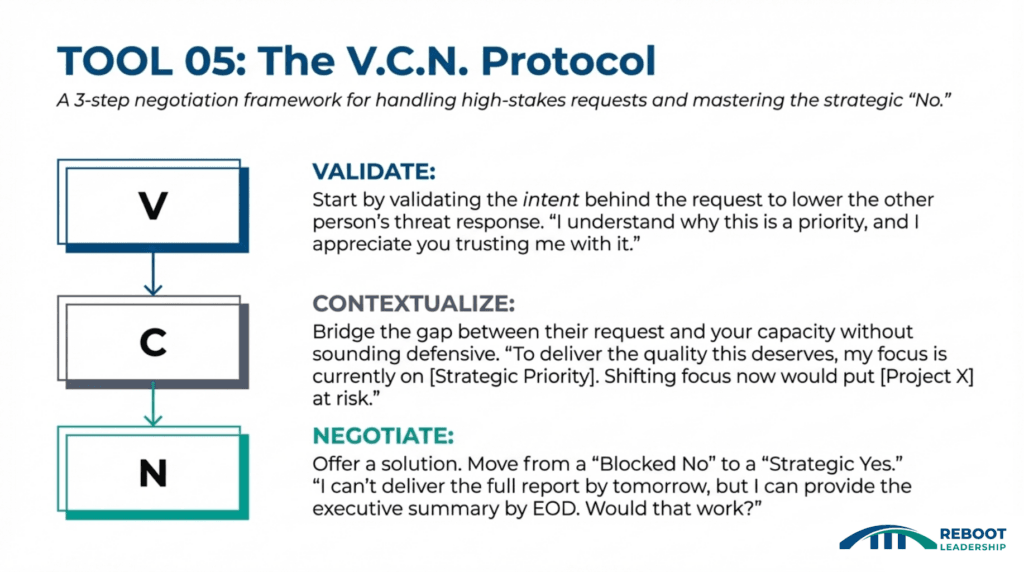

That’s what the V.C.N. Protocol is for.

What V.C.N. Actually Is

V.C.N. stands for Validate, Contextualize, Negotiate. It’s a communication framework for high-stakes conversations where you need to set boundaries without damaging relationships.

I didn’t discover this in a lab. It’s not a validated research model with empirical studies backing every component. What it is, though, is a synthesis of principles from multiple research domains that I’ve organized into a sequence that works for real leaders in real conversations.

The validation step draws from Mayer and Davis’s work on trust-building and threat reduction. When people feel heard, their defenses drop. It’s neuroscience.

The contextualization piece connects to expectancy violations theory and transparent communication research. You’re explaining the gap between what they asked for and what you can deliver without sounding defensive.

The negotiation element comes from Fisher and Ury’s interest-based bargaining. You’re solving for the underlying need, not just the surface request.

Each piece has a research foundation, but V.C.N. as a unified protocol is my contribution as a practitioner. I built it because leaders needed something simpler than reading five different research papers when they’re staring at an impossible deadline.

It works. It’s grounded in how humans actually build and maintain trust under pressure.

How V.C.N. Works: The Three Steps

Step 1: Validate – The “Yes” to the Person

The first step in any high-stakes conversation is to lower the other person’s threat response. If you start with “I can’t,” they stop listening. Their brain goes into defense mode, and everything you say after that gets filtered through resistance.

Validation isn’t agreement. It’s acknowledgment.

You’re saying: I see what you’re asking for. I understand why it matters. I’m not dismissing you.

This is where most people get it wrong. They think validation means lying or being fake. It doesn’t. It means separating the person from the request.

One of my clients was struggling to give feedback to a peer without triggering defensiveness. She kept trying to soften the message so much that the point got lost. When we worked on validation, she realized she could acknowledge her colleague’s intent before addressing the execution.

The shift looked like this:

Instead of: “This approach isn’t going to work.”

Try: “I can see you’re trying to solve for X, and I appreciate the thought you put into this.”

That’s it. You’ve validated the intent. Now you can address the gap.

The Script:

“I can see that this new timeline is important to you.”

“I understand why this data is critical for your upcoming board meeting.”

“I appreciate that you’re trying to move quickly on this.”

Notice what you’re NOT doing: You’re not agreeing to do what they asked. You’re agreeing that their need is real and their urgency makes sense from their perspective.

Step 2: Contextualize – The Transparent Reality

This is the pivot. You need to explain the gap between what they’re asking for and what you can actually deliver, without sounding defensive or making excuses.

The mistake most people make here is over-explaining. They list all the reasons why they can’t do something, which comes across as justification. Or they under-explain and sound dismissive.

Contextualization is about transparency, not justification.

You’re showing them the constraint. Not to make them feel bad, but to help them understand the trade-off they’re actually asking for.

I worked with a leader whose boss kept dismissing her detailed progress reports. The boss wanted big vision, big results. My client kept trying to explain all the work that was happening behind the scenes, and it wasn’t landing.

We shifted her approach. Instead of contextualizing the effort (which he didn’t care about), she contextualized the outcome (which he did).

Case A: The Progress Update

Instead of (The Weeds): “I spent the last three days cleaning up the spreadsheet because the formatting was broken, and I’m waiting on IT to fix the server permissions.”

Try (The Vision): “We are on track for the Q3 launch. I’m currently finalizing the data integrity to ensure the dashboard tells the story you want to present to the Board. I’ll have that ready for you on Tuesday.”

Same information. Different frame. One sounds like a problem. The other sounds like progress.

Case B: Managing a Delay

Instead of (The Excuse): “I can’t get this done by Friday because the team is overloaded and we don’t have the resources.”

Try (The Quality Pivot): “To deliver the result we discussed, I need to extend the timeline by 48 hours. This ensures the final product matches your standard, rather than being a rushed draft.”

You’re not hiding the constraint. You’re framing it as a commitment to quality, which is true.

Case C: Clarifying the Ask

Instead of (The Open Door): “What do you think about this report?”

This invites them to pick apart details, which might be too compelling for some leaders and too vague for others.

Try (The Guided Focus): “I’ve prepared the data for the strategic review. I’d value your input specifically on the executive summary slide. Does this capture the narrative you want to drive home?”

You’ve narrowed the scope. You’ve made it easier for them to give you useful feedback. You’ve also protected yourself from a fishing expedition.

Case D: Protecting Your Capacity

One of my clients kept getting pulled into last-minute meetings that derailed her entire day. She felt like saying no would make her look uncooperative, but saying yes was destroying her ability to do her actual job.

We worked on a contextualization script:

Instead of (The Hard No): “I can’t make that meeting.”

Try (The Capacity Truth): “I have a conflict at that time that I can’t move. If this is critical, I can review the notes afterward and follow up with questions. Would that work?”

You’ve shown the constraint. You’ve offered an alternative. You’ve made it their choice.

Step 3: Negotiate – The Minimum Viable Deliverable

Now that you’ve validated their need and explained the constraint, you offer a solution. This is where you move from “No, I can’t” to “Here’s what I can do.”

The key is offering something real, not a token gesture. You’re not trying to placate them. You’re trying to solve for the underlying need with what you actually have capacity to give.

One leader I worked with was constantly being invited to meetings where her role wasn’t clear. Instead of silently accepting the invites (The Default Yes) or declining them and looking uncooperative (The Hard No), she negotiated the terms of her engagement.

She responded to vague invites with: “What role do you see me playing in this meeting?”

This forced the requestor to define the need. Often, they realized she didn’t need to be there, or that her input could be handled via email. She saved time, but she also taught her organization how to treat her time with respect.

The Script:

“I cannot deliver the full report by Friday, but what I can do is provide a one-page executive summary of the key risks. Would that suffice for your meeting?”

“To ensure I can contribute meaningfully, could you send the agenda in advance? If it’s a general update, I can review the notes afterward.”

“I can’t take on the full project lead role right now, but I can facilitate the kickoff meeting and help you identify the right owner. Does that help?”

Notice the pattern: You’re not saying “No, figure it out yourself.” You’re saying No to this specific ask, but yes to solving the underlying problem in a different way.

Putting It All Together: The Full Scenario

Let’s walk through a real situation. Your boss just asked you to deliver a complex analysis by tomorrow morning. You know that’s not realistic without sacrificing quality or working until midnight.

Here’s how V.C.N. works in practice:

Boss: “I need the full competitive analysis ready for the leadership meeting tomorrow at 9am.”

You (Validate): “I understand this is important for your presentation. You want to make sure the team has the full picture.”

Boss: “Exactly. Can you get it done?”

You (Contextualize): “To deliver a complete analysis that includes the market data and the strategic recommendations, I need another 48 hours. If I rush it tonight, you’ll get surface-level insights, but not the depth you need to make a strong case.”

Boss: “But I need something for tomorrow.”

You (Negotiate): “What I can do is provide a one-page summary tonight with the top three competitive threats and our initial response framework. That gives you enough to anchor the conversation tomorrow. Then I’ll deliver the full analysis by Wednesday with all the supporting data. Does that work?”

Boss: “Yeah, that actually makes more sense. Send me the summary by 6pm.”

Notice what happened. You didn’t just say no. You didn’t capitulate and work all night. You validated the need, contextualized the constraint, and negotiated a solution that served both of you.

When V.C.N. Feels Impossible

If you’re reading these scripts and thinking “I could never actually say that,” you’re not alone.

One client told me: “It sounds like a lot of work when I’m already exhausted.”

Fair. You’re already carrying a heavy load. The idea of adding a communication framework on top of everything else feels like one more thing to manage.

But here’s the truth: You’re already having these conversations. You’re just having them poorly, or avoiding them entirely, which creates more work down the line.

V.C.N. doesn’t add work. It reduces the emotional labor of unclear boundaries.

If the scripts feel hard but doable, that’s just growth. That’s the discomfort of saying something true that you’ve been trained not to say.

If they feel impossibly hard, like if you’re convinced that setting any boundary will destroy your relationships, then you might be caught in something deeper. You might be caught in the empathy trap, where your care for others has eliminated your sense of agency.

If that’s you, start here: The Empathy Trap: When High Care Becomes Low Agency

The Bottom Line

The goal of leadership isn’t to say yes to everything. It’s to be a reliable steward of the organization’s resources, including your own capacity.

By using V.C.N., you teach your organization how to treat you: not as a pair of hands that accepts every task, but as a strategic partner who negotiates for the highest sustainable outcome.

That’s not selfish. That’s leadership.

If you’re struggling to recognize the pattern: Read The Empathy Trap: When High Care Becomes Low Agency

For the highest-stakes application of V.C.N.: Read The Strategic Deferral: How to Decline Advancement Without Derailing Your Career

- V.C.N. synthesis from: Mayer & Davis (trust-building), Burgoon (expectancy violations theory), Fisher & Ury (interest-based negotiation)

- Emotional labor (Hochschild, 1983; Grandey, 2000)

- Psychological contracting (Rousseau, 1995)

- Impression management (Goffman, 1959)

Pingback: The Empathy Trap – When High Care Becomes Low Agency - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Strategic Deferral – How to Decline Advancement Without Derailing Your Career - Amy Kay Watson