You have a team member who isn’t delivering. They seem disengaged, self-interested, or perhaps they are actively dropping the ball.

The instinct for most high-performing leaders is frustration. You look at the facts, the reality, and the obvious solution, and you wonder: Why won’t they just do the right thing?

When you feel this frustration, you are likely experiencing the Fundamental Attribution Error. This is a well-documented cognitive bias where we attribute our own failures to context (“I was late because traffic was terrible”), but we attribute others’ failures to their character (“They are late because they are disorganized”).

If you act on that bias, you will enter the conversation putting your foot down. You will trigger their defensiveness, and you will get compliance at best, but never commitment.

There is a better, evidence-based alternative. You don’t need to have “The Talk.” You need to run a Performance Diagnostic.

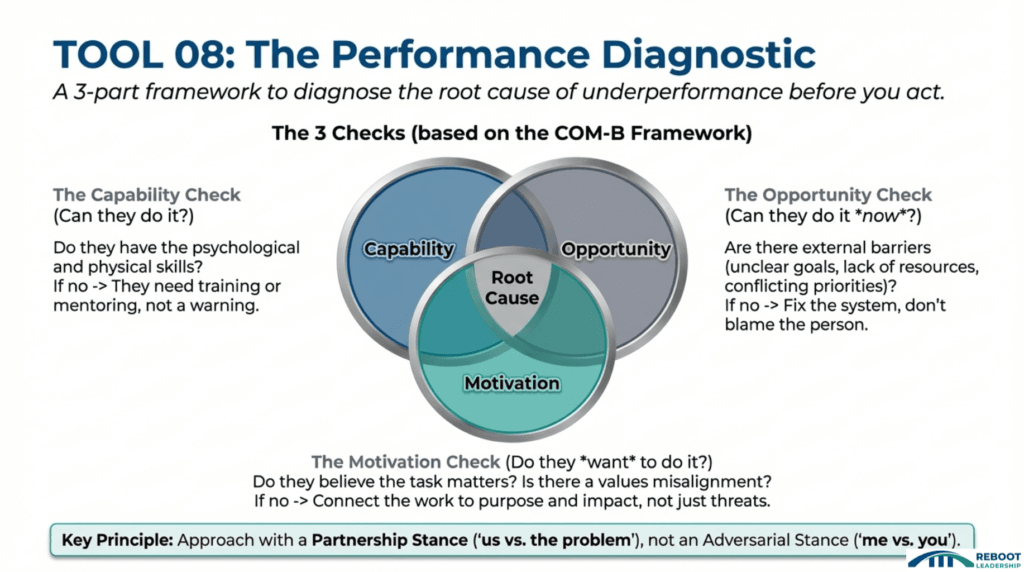

The 3-Part Diagnostic (The COM-B Framework)

Before you speak to the employee, you must pause and analyze the root cause of the behavior. Behavioral science suggests that performance is the result of three interacting factors: Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation.

Use these three questions to diagnose the gap:

1. The Capability Check (Can they do it?)

Do they possess the psychological and physical skills to do the job?

- The Trap: Assuming that because they did it once, they can do it under current stress levels.

- The Fix: If the answer is no, they don’t need a warning; they need training or mentoring.

2. The Opportunity Check (Can they do it now?)

Are there external barriers in the system preventing them from succeeding?

Case Study: The “Vacation” Misunderstanding One client I worked with was worried her direct report was treating remote work days as “travel time” or non-work time. Her initial instinct was to attribute this to a character flaw—a lack of dedication.

However, by pausing to diagnose the Opportunity gap, she clarified that the work on those days was mission-critical and already running behind schedule. The environment lacked the necessary structure for high performance.

Instead of accusing the employee of laziness (“The Talk”), she set a structural boundary to support the work: she requested end-of-day reports. This wasn’t a punishment; it was a structural tool to remove ambiguity. By addressing the Opportunity gap, she ensured accountability without assuming poor intent.

3. The Motivation Check (Do they want to do it?)

This is rarely about laziness. It is usually about alignment. Do they believe the task matters? Do they see the relevance?

Case Study: The Long-Tenured Resisters Another client needed to have difficult performance conversations with two long-tenured team members who were resistant to new management protocols. They had the skills (Capability) and the time (Opportunity), but they lacked the buy-in.

Instead of relying on “because I said so” (Compliance), the leader focused on Helping Them Care. She prepared the conversation to explicitly connect their lack of adherence to the downstream impact on the rest of the team and the future consequences of their choices.

She framed the expectations not as arbitrary rules, but as critical relevance to the team’s success. She diagnosed a Motivation gap and solved it with purpose, not threats.

The Conversation: Replacing Judgment with Inquiry

If you determine the employee has the Capability and the Opportunity, you are likely dealing with a Motivation gap. Traditional management says, “If you don’t change, I will write you up.” This threatens their safety and triggers a “fight or flight” response, shutting down the part of the brain responsible for learning.

To get true accountability, you must lower the threat level to increase the truth level.

Case Study: The Defensive Employee Bebe, a manager I coached, faced a recurring challenge with a defensive employee who constantly deflected blame. Her previous attempts to “correct” him likely triggered his defense mechanisms.

She decided to change her stance. Instead of confronting him with an accusation (Adversarial Stance), she shifted to reflective inquiry. She asked questions and invited him to describe what went wrong from his perspective.

Because she removed the threat, he felt safe enough to lower his shield. The result? He acknowledged his mistake voluntarily. Bebe’s empathy preserved his dignity, which actually allowed him to take accountability.

The “Positive Regard” Principle

In my coaching practice, I often tell leaders: To manage someone well, you have to hold them in Unconditional Positive Regard.

This doesn’t mean you have to be best friends with them. It means you must fundamentally believe that they are a rational human being doing their best given their current context.

- The Adversarial Stance: “They are broken, and I need to fix them or fire them.”

- The Partnership Stance: “We have a shared goal, and something is getting in the way. Let’s find it.”

When you approach a difficult conversation with the Partnership Stance, your tone changes. You move from “me vs. you” to “us vs. the problem.”

The Bottom Line High standards and high compassion are not mutually exclusive; in fact, they are interdependent. You cannot hold someone truly accountable if they are terrified of you.

- Diagnose before you judge (Check Capability, Opportunity, Motivation).

- Map the Impact (like the leader showing downstream effects).

- Partner with them to solve the block (like Laura using inquiry).

When expectations are clear and your intent is supportive, accountability becomes a tool for growth, not a weapon for compliance.

You can talk with me if you’re interested in exploring how coaching might support you in achieving your goals. I look forward to hearing what you have to say.

Pingback: Feeling Stuck as a Leader? Start Here – Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Promotion Trap: Why Management is a Career Change, Not a Step Up - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Architecture of Repair: A 5-Step Protocol to Operationalize Conflict Resolution - Amy Kay Watson