How to move your team from “who is to blame?” to “how do we fix it?” using restorative principles.

Conflict is not just an HR issue; it is operational drag. When trust fractures in a high-performing team, information flow slows down, decision-making creates friction, and innovation stalls.

Most managers default to one of two modes during conflict: Avoidance (hoping it blows over) or Arbitration (acting as a judge to determine who is right). Neither restores the flow of work.

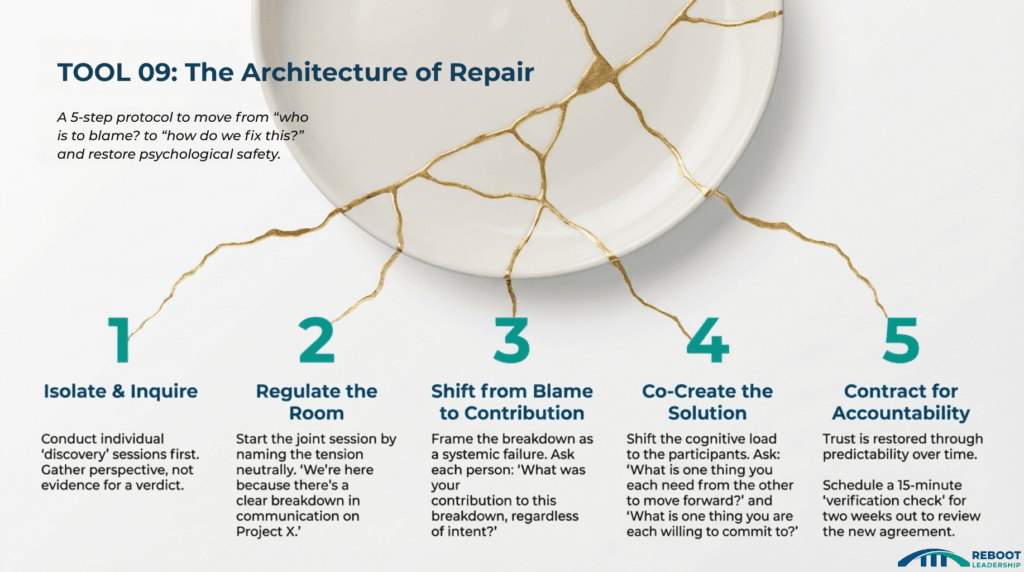

To rebuild trust, senior leaders must shift from a retributive mindset (punishment) to a restorative mindset (repair). Drawing on research from Restorative Justice and Trust Repair Theory, here is a 5-step protocol designed to restore psychological safety and operational capacity.

1. Procedural Justice: The Separate Intake

The Science: Research on Interactional Justice shows that people accept difficult outcomes if they believe the process was fair and they were heard. The Action: Before bringing parties together, conduct a “discovery phase” individually. The Shift: Do not gather evidence for a verdict. Gather perspective for a solution.

- Ask: “What is your experience of this situation?” and “What is the impact on your capacity to deliver results?”

- Why it works: High emotion creates “cognitive tunneling.” By listening without judgment in private, you lower the amygdala response, allowing the employee to access their logical reasoning skills before the joint meeting.

2. Affective Labeling: Calming the System

The Science: Neuroimaging studies (Lieberman et al.) demonstrate that “affective labeling”—putting feelings into words—diminishes the response of the amygdala. You cannot problem-solve while the brain is in threat mode. The Action: When you bring the team together, start by naming the “elephant in the room” neutrally.

- Say: “There is tension in the room regarding Project X, and it is creating a bottleneck. We are here to clear that bottleneck.”

- The Protocol: Invite each person to state the impact of the conflict on them, not the intent of the other person.

- Bad: “You were disrespectful.” (Accusation/Intent)

- Good: “When I didn’t receive the data by noon, I felt undervalued and I missed my own deadline.” (Impact)

3. Attribution Retraining: Owning the Contribution

The Science: We tend to attribute our own mistakes to the situation (context), but others’ mistakes to their character (fundamental attribution error). Trust repair requires shifting focus from character flaws to specific behaviors. The Action: Frame the breakdown as a systemic failure that requires individual ownership.

- The Script: “This isn’t about assigning blame. It’s about understanding the pattern so we don’t repeat it. What was your contribution to this dynamic?”

- Real-World Application: Ownership isn’t always about admitting you were “wrong”; often, it’s about admitting you were incomplete. For example, one manager found himself in a deadlock with a peer over a process change. He felt he was right, but the conflict persisted. Upon reflection, he realized his contribution to the friction wasn’t his opinion, but his lack of perspective: he hadn’t stopped to consider the operational challenges his colleague was facing. Acknowledging that gap broke the deadlock.

4. The Future Pact: Co-Creating Agreements

The Science: Self-Determination Theory suggests that people are more likely to adhere to rules they helped create. Imposed solutions rarely stick; co-created solutions build autonomy. The Action: Shift the cognitive load to the participants.

- Ask: “What specifically needs to happen differently next Tuesday for us to trust this process?”

- The Agreement: Move from vague promises (“I’ll do better”) to specific behavioral outputs (“I will update the Slack channel by 4 PM”).

- Note on Integrity: If the conflict involved an integrity violation (lying/stealing), research shows simple apologies do not work. The “penance” (Step 4) must be substantial and verifiable.

- Case Study in Repair: A manager of a contract worker felt a micro-rupture in trust; she feared her repeated Slack follow-ups were coming across as micromanagement. Instead of pulling back (avoidance) or doubling down (control), she used the friction to co-create a solution. She and the employee designed a shared project checklist.

- The Result: The checklist removed the need for constant pings. The conflict was resolved not by feelings, but by a better system.

5. Trust Verification: The Loop-Back

The Science: Trust is not restored in a single moment; it is restored through predictability over time. The Action: Schedule a 15-minute “verification check” for two weeks out.

- Say: “We will meet in 14 days to review these agreements. I am not looking for perfection, but I am looking for progress.”

- Why it works: This creates what is known as a “commitment device.” The knowledge of the upcoming meeting forces adherence to the new behavior. As one manager noted in a recent reflection, when a team member sees you paying attention, accountability shifts from “pressure” to “presence.”

Note on Delivery: Sometimes the conflict stems from a mismatch between message and tone. One leader realized her “approachable” tone was actually diluting the urgency of her requests, causing her team to miss deadlines. Naming this dynamic, “I realize I may have sounded casual, but this deadline is hard,” can instantly clear the air.

Executive Summary

You cannot “manage” emotions, but you can manage the architecture of the conversation. By moving from blame to contribution, and from punishment to repair, you treat conflict not as a personnel problem, but as a process failure to be engineered.

Pingback: The ‘Mirror’ and the ‘Report Card’: Why Most Career Assessments Fail - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Cognitive Pivot: How Senior Leaders Extract Value from Setbacks - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Promotion Trap: Why Management is a Career Change, Not a Step Up - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: Beyond “The Talk”: A Diagnostic Approach to Accountability - Amy Kay Watson