In 2023, 42% of workers reported feeling burned out, a statistic that had climbed steadily since 2020. But for senior leaders, the problem isn’t just the number of people burning out; it’s the type of people we are losing.

We are seeing seasoned veterans (the ones who usually “power through”) hitting a wall.

For years, the corporate narrative has treated burnout as a failure of individual resilience. We told leaders to “be like a duck” (calm on surface, paddling constantly underneath) or to simply practice better self-care. But when your highest performers start disengaging, it isn’t a resilience problem. It’s a physics problem.

The Myth of the “Lean” Organization

For decades, American business has been enamored with the “lean organization.” The goal was efficiency: remove the slack, tighten the timelines, and maximize output.

However, in mechanics, a system with zero slack is a system with zero shock absorption. When the Great Resignation hit, there was no buffer left. High performers like engineers and Scrum Masters stepped in to cover gaps, essentially “rescuing” the system. While heroic, this masked the structural fractures until the heroes themselves broke.

The Science: Demands vs. Resources

We need to upgrade our operating model from “stoic endurance” to Sustainable Performance.

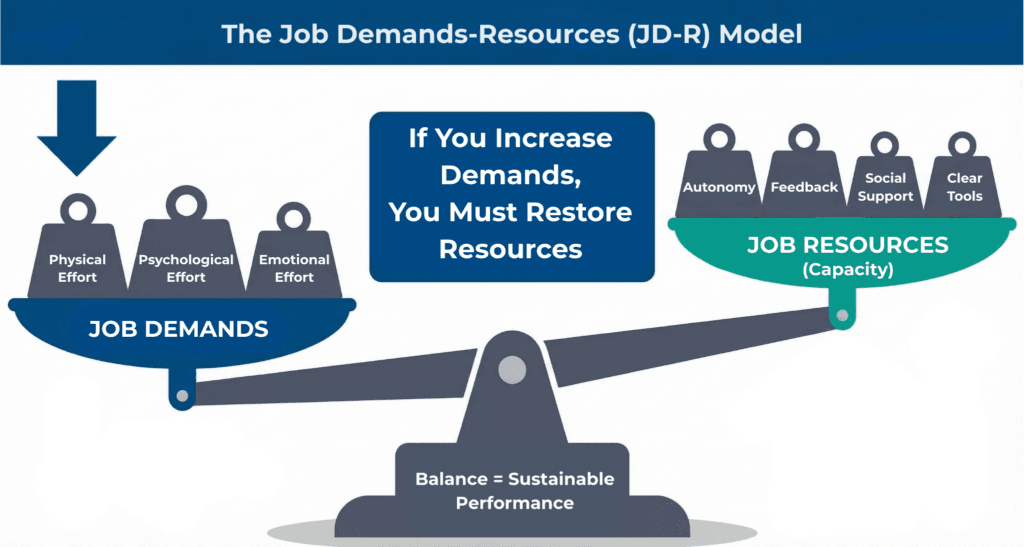

According to the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, one of the most validated frameworks in organizational psychology, burnout is not caused simply by hard work. High pressure is sustainable if it is matched by high resources.

- Demands: Workload, emotional pressure, complex problem-solving.

- Resources: Autonomy, role clarity, social support, and constructive feedback.

Burnout occurs when Demands outweigh Resources for a sustained period.

When we cut “inefficiencies” like administrative support, redundant staff, or “buffer time” between projects, we are often stripping away the very resources that allowed your people to handle the high demands.

The Executive Function Deficit

Why should a bottom-line-focused leader care? Because burnout is a biological impairment. It creates a functional deficit in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for strategic planning, emotional regulation, and complex decision-making.

A burned-out leader isn’t just “tired.” They are cognitively compromised. They are more likely to make impulsive decisions, struggle with nuance, and fail to anticipate risks.

The Leader’s New Role: Resource Architect

Prioritizing mental health doesn’t mean lowering your standards. It means securing the supply lines for your team’s energy.

We see this in leaders who shift from “policing” to “partnering.” One client of mine noticed her project managers were hoarding problems, trying to be “fixers.” By resetting expectations, clarifying that their job was to escalate risks, not absorb them, she reduced their cognitive load without reducing the team’s output. She increased their resources (role clarity) to match their demands.

From Hero to Architect

Many leaders fall into the trap of being the “Shock Absorber.” One middle manager I worked with deliberately positioned herself as a human shield between unrealistic executive demands and her team. Her logic was noble: “The pressure won’t go away, but I can’t keep pushing them forever.”

While heroic, this is bad physics. A shock absorber eventually wears out. When that leader breaks (and she will) the shock transfers instantly to a team that has developed no resilience of its own. The goal isn’t to take the heat for your team; it’s to build a structure where the heat is distributed and manageable.

Why Leaders Stay Stuck as Shock Absorbers

If the physics are so clear, why do smart leaders keep absorbing all the drag?

Often, it’s because we’ve confused empathy with avoidance. We think, “I don’t want to be harsh,” so we don’t hold the difficult conversation. We fix the errors ourselves. We shield the team from feedback they need to hear.

But empathy without accountability isn’t kindness. Instead, it’s negligence. And it’s expensive. The leader who “takes the heat” so her team doesn’t have to isn’t protecting them; she’s preventing them from developing the capacity to handle heat themselves.

Sustainable leadership requires both: the empathy to understand what your people are carrying, and the accountability to address what isn’t working. That’s how you stop being the shock absorber and start being the architect.

3 Questions to Audit Your Team’s Physics

Instead of asking your team to “be more resilient,” ask yourself these questions about your organizational design:

- The Autonomy Check: Do my people have the authority to make decisions proportional to the responsibility I’ve given them? (High responsibility + Low control = High Burnout).

- The Drag Audit: Where are we wasting cognitive energy?

- Burnout often hides in the tools we use to manage it. One leader I coached was tracking her division’s status in a massive, color-coded Word document. She was meticulous, but the sheer size of the file meant she began avoiding it entirely. The tool she built to create control was actually creating cognitive overload.

- Ask yourself: Are our processes acting as a lever that multiplies effort, or drag that consumes it? If your leaders are spending more energy managing the work than doing the work, you have a physics problem.

- The Recovery Protocol: Do we view recovery as “time off” (absence of work) or as “strategic refueling” (presence of restoration)?

Bottom Line: The world needs leaders who are healthy enough to handle complexity. As much as I truly wish we could, it turns out we can’t achieve that by simply telling people to “be good to each other.” We achieve it by building organizations that respect the biological limits of human performance.

Efficiency matters. But sustainable efficiency requires a system that recharges as effectively as it depletes.

You cannot “self-care” your way out of a broken workflow.

If you recognized your organization in this article, it is time to move from “resilience” to “architecture.”

I have compiled a Physics of Burnout Protocol to help you diagnose the system failure.

Inside this downloadable toolkit:

- The Physics One-Sheet: Scripts to negotiate capacity without sounding “weak.”

- The Drag Audit: A diagnostic tool to spot cognitive energy leaks.

- The “Protect the Asset” Matrix: A decision framework for high-stakes leaders.

image generated by DALL-E

Pingback: The Strategic Pause: Mastering the High-Stakes “No.” - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The High-Performer’s Trap: “Polishing” is Killing Your Progress - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Promotion Trap: Why Management is a Career Change, Not a Step Up - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: Empathetic Accountability Done Right Prevents Leader Burnout - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Confidence Trap: Why Smart Leaders Leverage Strategic Doubt - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Solitary Executive: Why Strategic Support is an Operational Necessity - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: How Emotional Self-Awareness and the Mood Elevator Transformed My Career - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: Connecting the Dots: Why I’ve Been Obsessed with the PIP (and What Comes Next) - Amy Kay Watson