It feels good to be the one with the answers.

A team member comes to you with a crisis—a conflict between departments, a technical stall, or a budget issue. You have the experience, so you jump in. You make the call, you smooth the ruffled feathers, you fix the spreadsheet. The crisis is averted, and your team thanks you.

But then it happens again. And again.

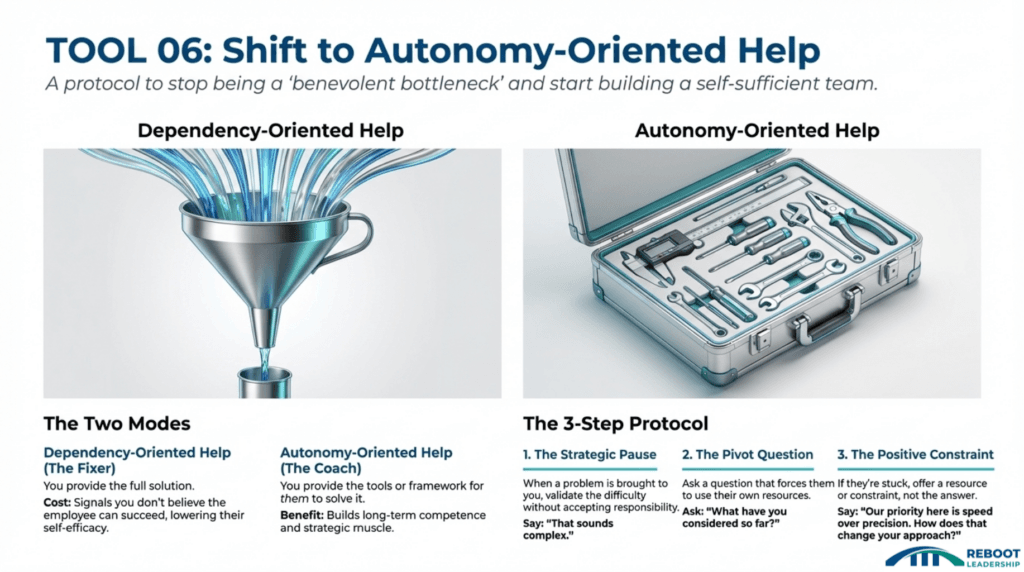

If you find yourself constantly solving problems you thought you hired other people to solve, you might be falling into a common leadership trap. In the psychological literature, this is the difference between Dependency-Oriented Help and Autonomy-Oriented Help.

Understanding the distinction is the key to moving from an exhausted “fixer” to a scalable leader.

The Two Types of Help

Research by psychologist Arie Nadler identifies two distinct ways we assist others:

Dependency-Oriented Help: You provide the full solution. You give the man a fish. This is efficient in the short term because the problem goes away immediately. However, it has a hidden cost: it signals that you don’t believe the employee can solve the problem themselves. Over time, this lowers their “self-efficacy”—their belief in their own capability—and trains them to come to you for everything.

Autonomy-Oriented Help: You provide the tools, the framework, or the question that allows them to solve the problem. You teach the man to fish. This takes more time upfront and requires patience, but it builds competence and prevents the problem from bouncing back to your desk.

When we habitually use Dependency-Oriented Help, we become Benevolent Bottlenecks. We mean well—we want to support our team—but we actually cap their growth and ensure that all complex cognition has to route through us.

The Unintended Signal

Consider a scenario: Two Directors, Sheila and Otto, are fighting over resources. They bring the problem to you.

The Benevolent Bottleneck (You): “Okay, look, just split the budget 50/50 this quarter and we’ll review it in Q3.”

The Signal: “You two are incapable of negotiation. I am the only adult in the room.”

The Autonomy Builder (You): “I see the conflict. Based on our Q3 strategic goals, what criteria do you two think we should use to prioritize this spend?”

The Signal: “I trust you to align with the strategy and solve this.”

The first approach solves the budget issue but keeps Sheila and Otto dependent on you as a referee. The second approach might take a 20-minute meeting, but it builds their strategic muscles.

Case Study: The Trap of the Heroic Fixer

Consider a real example from a client I’ll call Natalie, a leader in a technical organization. Natalie was receiving heat from her stakeholders because project risks were being flagged too late. When the explosion happened, it was massive.

When Natalie dug into the root cause, she didn’t find laziness. She found helpfulness.

Her Project Managers were natural “fixers.” When a technical hurdle appeared, they viewed it as their job to jump in, smooth it over, and solve it immediately. They were practicing Dependency-Oriented Help. They thought they were protecting the timeline.

In reality, they were masking the signal.

Because they “rescued” the project daily, the data regarding the actual risks never made it to the dashboard. By the time the problem became too big for them to fix alone, it was too late for leadership to pivot.

Natalie had to teach her team a counter-intuitive lesson: Sometimes, the most supportive thing you can do is let the red flag fly.

The Benevolent Bottleneck Move: “I’ll handle this glitch so the stakeholders don’t worry.”

Result: False sense of security; catastrophic late failure.

The Autonomy-Oriented Move: “This glitch threatens the critical path. I will escalate it immediately with a proposed solution so we can adjust resources.”

Result: Transparent risk; collective problem solving.

Natalie’s team stopped trying to be heroes and started being leaders. The “noise” in the system went up, but the late-stage explosions went down.

How to Stop “Fixing” and Start Leading

Breaking the habit of immediate fixing is difficult because fixing gives us a dopamine hit. We feel useful. We feel heroic. But to scale your leadership, you must trade that quick hit for the long-term satisfaction of team growth.

Here is a practical protocol to shift from Dependency to Autonomy:

1. The Strategic Pause When a direct report brings you a “monkey” (a problem that belongs to them), do not immediately pick it up. Take a breath. Validate the difficulty of the situation without accepting responsibility for it.

Say: “That sounds like a complex situation.”

2. The Pivot Question Instead of offering a solution, ask a question that forces them to access their own problem-solving cognitive resources.

Ask: “What have you considered trying so far?” or “What is your proposed next step?”

3. The Positive Constraint If they are truly stuck, offer a constraint or a resource, not the answer.

Say: “I can’t make that decision for you, but I can tell you that our priority right now is speed over precision. How does that change your approach?”

The Leader’s Role

Your value as a senior leader is no longer defined by how many fires you put out. It is defined by how many fire chiefs you develop.

Stepping back isn’t about abandonment; it’s about active, strategic support. By refusing to provide the quick fix, you are doing the harder, more supportive work of ensuring your team is ready for the challenges ahead.

So, the next time you are tempted to save the day: Stop. Pause. And ask them what they plan to do next.

Pingback: Breaking the Reformer’s Trap: Balance Empathy & Accountability - Amy Kay Watson

Pingback: The Physics of Burnout: Why “Efficiency” is Costing You Your Best Decisions - Amy Kay Watson